- Home

- Bryn Hammond

Of Battles Past (Amgalant #1) Page 9

Of Battles Past (Amgalant #1) Read online

Page 9

People come to watch.

The brothers muttered to each other that they were glad, they were proud Oikon had been there with Ambaghai. Cutula observed, “It’s a chancy thing, to mock. You try for contempt, and contempt blows back in your face.”

“I hear Ambaghai sat indifferent to them, his eyes on the horizon. Oikon sang.”

“They were faced towards north – did you know?”

“Were they?” He gleamed, almost smiled. “Why?”

“Ignorance? Our saints in the sky.”

“Mockery. Ride home if you can.”

“Mockery.” Cutula nodded. “Like I said. In your face.”

Meanwhile Galut wept, on their behalf. Also she pulled them back to the here and now, the daily and mundane, and consulted Bartan in the outfitting of her husband. “I thought, with eyes on him so, he might have me sew up a new suit of clothes for him.”

“A new suit of clothes?” blustered Cutula. “You can sew me new clothes in the winter and bless you. I don’t go into the year’s clothes early, for eyes. And consider, Galut.” Much quieter. “They’d say I’m on the scent.”

“You are on the nose,” she told him promptly.

Bartan, left the family umpire, on age, said that skins from one’s own sheep can never be undignified... and Cutula didn’t want to turn this into a beauty contest.

In a big glade of the willow growth at dawn they gathered for a memorial, or funeral for the absent. It was kept very simple. First Ambaghai’s message was heard, through his Besut who had escaped from under the very shadow of the Wall, no easy matter and not without incident, Bartan believed. This Besut hadn’t been a wedding-guest, he had gone along to lead the string of spare mounts; he was black-boned – of obscure ancestry – or black-headed, that is a man with his hair in its native state who doesn’t wear a hat. Besut were a slave tribe of Tayichiut. As punishment for his services he had been stood up on a rock amid a sea of the noblest hats, with instructions to use his tongue. The man failed miserably at first.

Into the silence of stage-fright a voice shouted out, with a verve meant to be infectious, smacking the lips over the syllables. “Balaqachi Baghatur.”

The moot shout. You’re only allowed to shout the once. But he got a second, and a third distinct, and after that he got a bawl. Maybe sentiment crept in – Bartan hadn’t heard about an actual tally of the slain – but he had brought them Ambaghai’s last words. Now Attai leapt onto the rock, and in the gift that comes most straight and sincere from the heart, clothes instinct with the odour of the giver (an intimacy, a brotherhood) he draped on Balaqachi’s shoulders his own gilt coat. Aristocracy, ancestry? Not there lies pride, for a Mongol. Shout him a hero, and he’ll thrill to the shout for his life. Enheroed, and with Attai’s hand on his newly-splendid shoulder, Balaqachi heaved in air and spoke strong enough.

“This was I to convey to Cutula son of Khabul and to Attai son of Ambaghai: My daughter and I went amongst the Tartars to her wedding and were seized. I am about to go behind the Wall. Don’t commit my mistake, when you are chief over chiefs, khan of our people. Until your five nails are torn off, until your ten fingers worn down, strive after my hachi.”

Hachi means that which is owed, or felt due. It can mean an act of humanity. It can mean vengeance. It meant justice.

His message was new to no-one there. Yet it had a terrific effect, heard together, direct from the mouth of his last contact with them. Undemonstrative men groaned, and stamped, and caught each other’s eye begging for a throat to slit. Bartan, blooded forty years ago and tough as an old boot, because he could not stand it, fumbled out a knife, turned down his fur cuffs to his fingers’ ends, and unseen gashed his hand.

Possessions of Ambaghai’s such as he might be interred with were laid on the rock. People hung their belts about their necks, removed hats and circled nine times. They left locks of white hair at the foot of the rock or flowers, coins or amulets or other little treasures, or a trickle of blood.

To be out of the way, Attai and Cutula began to study maps in a shut tent, ahead of the campaign.

People either liked the fact that Cutula had twenty years on Attai, or else they thought Attai had the cut of his father. There the wheels ground to a halt. “You’re entitled to your opinion,” said Heavenly Hair the Jajirat. “I’m entitled to mine. What do we do next?”

“Argue,” a friend of his told him.

Heavenly Hair crossed his arms. “I can fight you. I can’t argue with you. Haven’t had an argument in my life. If it’s not worth a feud, it’s not worth a loud voice.”

“Debate, then.”

“Debate what? You’re entitled to your opinion. I have no desire to change your mind.”

“You stubborn git. We can sit here side by side and opine our own opinions. That doesn’t get us a khan.”

“No, but it’s very nomad. And even more Mongol. What is a Mongol? – as my comrade’s old dad used to ask.” His comrade Bartan. “As free as the geese in the air, as in unison. Geese don’t argue. Only over she-geese, and I’m past that.”

“No, you’re not.”

“No, I’m not, either. Thanks be to ayrag. Liberty and loyalty, said my comrade’s old dad: learn from the geese, they can go together. They belong together. The flights of the geese promise us we don’t give up independence, to unite. Fine hand with an instructive simile, the old chief.”

Yes, he had been. What is a Mongol? Khabul rustled up answers to suit. The one dearest to him was the shortest: what is a Mongol? Loyal. Mongols were an invention of his, largely. And of themselves, for the habit had grown general, to ask and answer the question.

What is a khan? Not Mongol but steppe, antique steppe, Khabul the first Mongol to take the title. Before him they had elected temporary over-chiefs in time of war, Qaidu the lion of these, who had lived and led them in desperate times. Times that taught them, at last, Ulun Ghoa’s lesson: disunity is fatal. A permanent king, to be a symbol and guarantor of unity. Strong peoples have kings. It is a truth.

“The tribes of Israel clamoured for a king. Quoth Jehovah, Have I not been sufficient unto you? Other nations have kings, said the people, and we need to be strong against our enemies. Quoth Jehovah, Set a king above you and he’ll conscript your sons to run before his chariot, your daughters to bake his bread and perfume him; he’ll tithe your flocks, your olive groves, your orchards to pay the expenses of his court; you’ll find yourselves his slaves. On that day, because of the king you have got you, you shall cry out, but Jehovah will not hear.”

Bartan had a crony who had spent years among the Turks and gone half-Christian. “What was the upshot?”

“In short? God lost the argument, and through his prophets anointed kings. David, a hero-king, won the tribes’ war of liberation; King Solomon the Wise enriched and enlightened his people. After them the tale drops off. There’s a sad parade.”

“What Jehovah said of kings?”

“Too often true.”

Bartan harumphed. “We aren’t the tribes of Israel.”

“No indeed. – I dare be sworn your brother’s proof against magnificence. If magnificence hit your brother over the head, he’d blink about him and go back to scratch his fleas. Fat fleas, who scamper to hide in his creases.”

“Your vote’s his, then?”

“It’s why we love him. Seriously, Attai’s there for sentiment, isn’t he?”

An aged Tayichiut put a suggestion. “We go out to the horses and pluck a tail hair: for Cutula a light hair, for Attai a dark. We tie the hairs in bunches and the bunches’ size tells the mind of the people. That’s Qatat.” He went on, “Qatat have traditions alike to ours. They are known egalitarian. Chiefs of the eight tribes voted in an over-chief for a term of three years; at end of term he stepped down for a new vote.”

“Until one of them stopped the stepping down. When he hadn’t stepped down for three terms and disgruntlement grew severe, he invited the seven other chiefs to his joint for an election and had them murdered.

”

“This is so. But I talk of Qatat traditions.”

People weren’t content. “Two bunches of hair tell us we are of divided mind. A majority isn’t a unity.”

“How can we have a unity?”

“How can we not? Say Attai wins by a hair. First mistake he makes, we’ll have the Cutula I-told-you-sos.”

“Doesn’t seem fair on either of them. Our man deserves to know he has our support, not fifty-one per cent thereof.”

Thought continued. “A contest between them? For an outcome out of our hands, past dispute.”

“A duel? Lovely. Maybe on games day.”

“No, of course not a duel.”

“Rhyme and riddles, then? Or hit your target through your knees?”

“It’s Attai for hit-your-target, or any acrobatics, and he’d ravish hearts while he’s about. But it’s Cutula for pop heads off with your hands.”

“Can we get away from amusements? Here’s an amusement more seemly, from the Turks. When kings meet on affairs of state, they have a bilig contest as a gracious after-dinner pastime: which of them can spout most wisdoms. A bit like a flyte, only not insults. Wisdoms, the sport of kings.”

“Even wisdoms. I can quote old saws til the cows come home. Doesn’t make me material.”

A Noyojin said, “Duel is verdict-by-God. He’s onto an idea, ah –?”

“Natti.”

“Natti’s onto an idea, with his contests. Which are never just skill, but judgement of fortune or fate. We won’t put our

The brothers muttered to each other that they were glad, they were proud Oikon had been there with Ambaghai. Cutula observed, “It’s a chancy thing, to mock. You try for contempt, and contempt blows back in your face.”

“I hear Ambaghai sat indifferent to them, his eyes on the horizon. Oikon sang.”

“They were faced towards north – did you know?”

“Were they?” He gleamed, almost smiled. “Why?”

“Ignorance? Our saints in the sky.”

“Mockery. Ride home if you can.”

“Mockery.” Cutula nodded. “Like I said. In your face.”

Meanwhile Galut wept, on their behalf. Also she pulled them back to the here and now, the daily and mundane, and consulted Bartan in the outfitting of her husband. “I thought, with eyes on him so, he might have me sew up a new suit of clothes for him.”

“A new suit of clothes?” blustered Cutula. “You can sew me new clothes in the winter and bless you. I don’t go into the year’s clothes early, for eyes. And consider, Galut.” Much quieter. “They’d say I’m on the scent.”

“You are on the nose,” she told him promptly.

Bartan, left the family umpire, on age, said that skins from one’s own sheep can never be undignified... and Cutula didn’t want to turn this into a beauty contest.

In a big glade of the willow growth at dawn they gathered for a memorial, or funeral for the absent. It was kept very simple. First Ambaghai’s message was heard, through his Besut who had escaped from under the very shadow of the Wall, no easy matter and not without incident, Bartan believed. This Besut hadn’t been a wedding-guest, he had gone along to lead the string of spare mounts; he was black-boned – of obscure ancestry – or black-headed, that is a man with his hair in its native state who doesn’t wear a hat. Besut were a slave tribe of Tayichiut. As punishment for his services he had been stood up on a rock amid a sea of the noblest hats, with instructions to use his tongue. The man failed miserably at first.

Into the silence of stage-fright a voice shouted out, with a verve meant to be infectious, smacking the lips over the syllables. “Balaqachi Baghatur.”

The moot shout. You’re only allowed to shout the once. But he got a second, and a third distinct, and after that he got a bawl. Maybe sentiment crept in – Bartan hadn’t heard about an actual tally of the slain – but he had brought them Ambaghai’s last words. Now Attai leapt onto the rock, and in the gift that comes most straight and sincere from the heart, clothes instinct with the odour of the giver (an intimacy, a brotherhood) he draped on Balaqachi’s shoulders his own gilt coat. Aristocracy, ancestry? Not there lies pride, for a Mongol. Shout him a hero, and he’ll thrill to the shout for his life. Enheroed, and with Attai’s hand on his newly-splendid shoulder, Balaqachi heaved in air and spoke strong enough.

“This was I to convey to Cutula son of Khabul and to Attai son of Ambaghai: My daughter and I went amongst the Tartars to her wedding and were seized. I am about to go behind the Wall. Don’t commit my mistake, when you are chief over chiefs, khan of our people. Until your five nails are torn off, until your ten fingers worn down, strive after my hachi.”

Hachi means that which is owed, or felt due. It can mean an act of humanity. It can mean vengeance. It meant justice.

His message was new to no-one there. Yet it had a terrific effect, heard together, direct from the mouth of his last contact with them. Undemonstrative men groaned, and stamped, and caught each other’s eye begging for a throat to slit. Bartan, blooded forty years ago and tough as an old boot, because he could not stand it, fumbled out a knife, turned down his fur cuffs to his fingers’ ends, and unseen gashed his hand.

Possessions of Ambaghai’s such as he might be interred with were laid on the rock. People hung their belts about their necks, removed hats and circled nine times. They left locks of white hair at the foot of the rock or flowers, coins or amulets or other little treasures, or a trickle of blood.

To be out of the way, Attai and Cutula began to study maps in a shut tent, ahead of the campaign.

People either liked the fact that Cutula had twenty years on Attai, or else they thought Attai had the cut of his father. There the wheels ground to a halt. “You’re entitled to your opinion,” said Heavenly Hair the Jajirat. “I’m entitled to mine. What do we do next?”

“Argue,” a friend of his told him.

Heavenly Hair crossed his arms. “I can fight you. I can’t argue with you. Haven’t had an argument in my life. If it’s not worth a feud, it’s not worth a loud voice.”

“Debate, then.”

“Debate what? You’re entitled to your opinion. I have no desire to change your mind.”

“You stubborn git. We can sit here side by side and opine our own opinions. That doesn’t get us a khan.”

“No, but it’s very nomad. And even more Mongol. What is a Mongol? – as my comrade’s old dad used to ask.” His comrade Bartan. “As free as the geese in the air, as in unison. Geese don’t argue. Only over she-geese, and I’m past that.”

“No, you’re not.”

“No, I’m not, either. Thanks be to ayrag. Liberty and loyalty, said my comrade’s old dad: learn from the geese, they can go together. They belong together. The flights of the geese promise us we don’t give up independence, to unite. Fine hand with an instructive simile, the old chief.”

Yes, he had been. What is a Mongol? Khabul rustled up answers to suit. The one dearest to him was the shortest: what is a Mongol? Loyal. Mongols were an invention of his, largely. And of themselves, for the habit had grown general, to ask and answer the question.

What is a khan? Not Mongol but steppe, antique steppe, Khabul the first Mongol to take the title. Before him they had elected temporary over-chiefs in time of war, Qaidu the lion of these, who had lived and led them in desperate times. Times that taught them, at last, Ulun Ghoa’s lesson: disunity is fatal. A permanent king, to be a symbol and guarantor of unity. Strong peoples have kings. It is a truth.

“The tribes of Israel clamoured for a king. Quoth Jehovah, Have I not been sufficient unto you? Other nations have kings, said the people, and we need to be strong against our enemies. Quoth Jehovah, Set a king above you and he’ll conscript your sons to run before his chariot, your daughters to bake his bread and perfume him; he’ll tithe your flocks, your olive groves, your orchards to pay the expenses of his court; you’ll find yourselves his slaves. On that day, because of the king you have got you, you shall cry out, but Jehovah will not hear.”

Bartan had a crony who had spent years among the Turks and gone half-Christian. “What was the upshot?”

“In short? God lost the argument, and through his prophets anointed kings. David, a hero-king, won the tribes’ war of liberation; King Solomon the Wise enriched and enlightened his people. After them the tale drops off. There’s a sad parade.”

“What Jehovah said of kings?”

“Too often true.”

Bartan harumphed. “We aren’t the tribes of Israel.”

“No indeed. – I dare be sworn your brother’s proof against magnificence. If magnificence hit your brother over the head, he’d blink about him and go back to scratch his fleas. Fat fleas, who scamper to hide in his creases.”

“Your vote’s his, then?”

“It’s why we love him. Seriously, Attai’s there for sentiment, isn’t he?”

An aged Tayichiut put a suggestion. “We go out to the horses and pluck a tail hair: for Cutula a light hair, for Attai a dark. We tie the hairs in bunches and the bunches’ size tells the mind of the people. That’s Qatat.” He went on, “Qatat have traditions alike to ours. They are known egalitarian. Chiefs of the eight tribes voted in an over-chief for a term of three years; at end of term he stepped down for a new vote.”

“Until one of them stopped the stepping down. When he hadn’t stepped down for three terms and disgruntlement grew severe, he invited the seven other chiefs to his joint for an election and had them murdered.

”

“This is so. But I talk of Qatat traditions.”

People weren’t content. “Two bunches of hair tell us we are of divided mind. A majority isn’t a unity.”

“How can we have a unity?”

“How can we not? Say Attai wins by a hair. First mistake he makes, we’ll have the Cutula I-told-you-sos.”

“Doesn’t seem fair on either of them. Our man deserves to know he has our support, not fifty-one per cent thereof.”

Thought continued. “A contest between them? For an outcome out of our hands, past dispute.”

“A duel? Lovely. Maybe on games day.”

“No, of course not a duel.”

“Rhyme and riddles, then? Or hit your target through your knees?”

“It’s Attai for hit-your-target, or any acrobatics, and he’d ravish hearts while he’s about. But it’s Cutula for pop heads off with your hands.”

“Can we get away from amusements? Here’s an amusement more seemly, from the Turks. When kings meet on affairs of state, they have a bilig contest as a gracious after-dinner pastime: which of them can spout most wisdoms. A bit like a flyte, only not insults. Wisdoms, the sport of kings.”

“Even wisdoms. I can quote old saws til the cows come home. Doesn’t make me material.”

A Noyojin said, “Duel is verdict-by-God. He’s onto an idea, ah –?”

“Natti.”

“Natti’s onto an idea, with his contests. Which are never just skill, but judgement of fortune or fate. We won’t put our

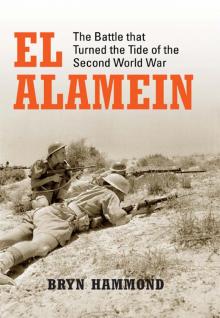

El Alamein

El Alamein